SINGAPORE – It felt like the start of a high-stakes contest for Mr Harry Lee when his son Gabriel entered Primary 1 in 2022.

Gabriel was an SG50 baby, referring to those born in 2015 when Singapore celebrated its 50th year of independence. More than 37,000 babies were born that year – the highest number recorded between 2015 and 2024 – possibly resulting in greater competition for school places.

The registration process has several stages, with the earlier ones reserved for children with siblings in the school or parents who are alumni. These were not options for Gabriel.

So Mr Lee aimed for Phase 2B, which gives priority to children whose parents have volunteered at the school. They were hoping to enter a popular school in Hougang where the family lives because of its academic reputation and emphasis on values.

“Every day that we were on traffic warden duty counted as 45 minutes to these 40 hours, and we went once a week for 40 weeks,” said Mr Lee, who clocked his time mostly in the morning before work. Parents were required to fulfil at least 40 hours to be considered a parent volunteer. “The school did not guarantee us a spot, they told us it is not confirmed.”

“That year was very stressful for us,” said Mr Lee, 44, an actuary at an insurance company.

Gabriel eventually entered the school through Phase 2B. While Mr Lee acknowledged that competition exists in every education system, he felt much of the stress stems from uncertainty.

Clearer indicators of a child’s likelihood of getting a place – beyond historical balloting data – would help parents better gauge their odds in the current year, he said.

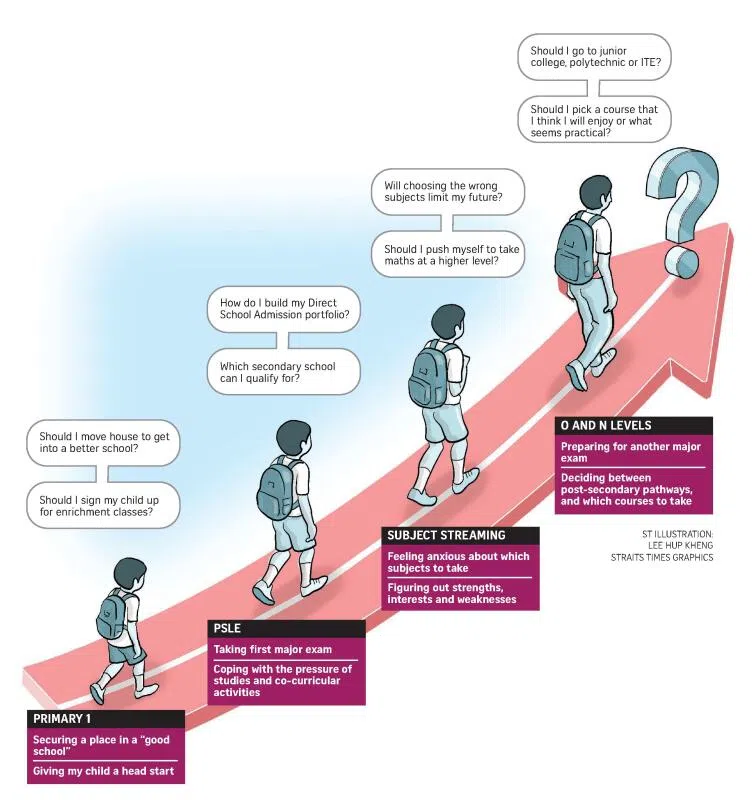

His experience is one of several pain points that parents face when navigating Singapore’s education system.

ST ILLUSTRATION: LEE HUP KHENG

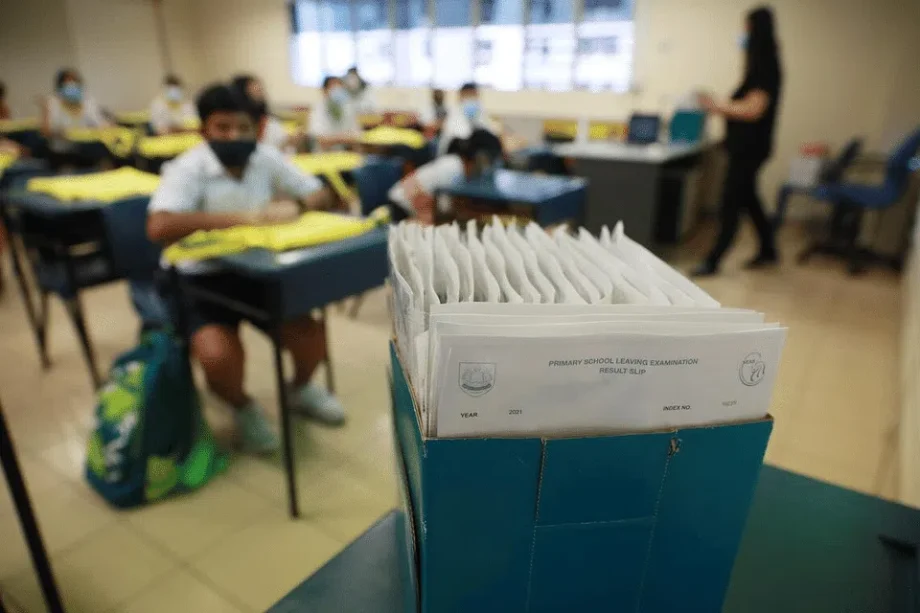

Others point to an overemphasis on major exams, starting with the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE), a competitive culture between parents, and heavy time and financial resources poured into getting outside-school help.

Long heralded as a meritocratic engine and a “social leveller”, the system has increasingly been described as an “arms race” by parents, students, educators, and politicians alike.

This is despite significant changes by the Government over the last five-year term, including the end of streaming and bell-curved scoring at the PSLE, which graded pupils’ performance relative to one another.

Ahead of the May general election, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong had said during the Fullerton Rally that reforms in education have been made, along with enhancing parental leave and other investments in mental health and caregiving.

MPs from both the PAP and WP said they will continue to push for reforms in the House, including exploring alternatives to the PSLE, smaller class sizes and more support for educators.

But experts outline the challenge at hand: the Government having to push through changes while ensuring the system continues to deliver good results, and balancing the various interests from across society, making the issue a political hot potato.

Parents interviewed by Insight said navigating school life feels like running a race they cannot opt out of.

Some map out their children’s educational paths years ahead, while others turn to tuition and enrichment while trying to clinch spots in popular schools.

Students report stress over examinations and expectations, with some feeling their self-worth is tied to grades or the school they go to.

Political leaders have acknowledged the issue – during the debate on the President’s Address in September, PM Wong said the Government will do more in its new term to

reduce the stakes of single examinations,

and that Singapore has to move from a narrow meritocracy based solely on grades to a broader and more inclusive one.

Noting that education was a “great leveller” for his generation, he said that looking ahead, every parent and child should not regard it as a burden, but a springboard.

At the same debate, Education Minister Desmond Lee said Singapore must break away from seeing education as an “arms race”.

His ministry will study how to reduce the stakes in exams, focus on non-academic aspects of the school experience, and guard against “hothousing” by families with more resources.

For many families, however, the race remains a daily reality. The first major hurdle is the PSLE, which determines the range of secondary schools a child can enter.

Ms Jyoti Khan, a mother of three, said the pressure of the system is “almost contagious”. When her children first entered primary school, she did not know how intense the journey could become.

By the time her older two had sat the PSLE, she found herself swept into the rhythms that govern so many families’ lives – sending her kids for tuition and planning the year around exams.

“All your peers, every parent, will be talking about ‘Oh, it’s a big year because it’s O levels, or it is a big year because it’s PSLE’, and you feel yourself joining in a little bit,” the 47-year-old communications consultant said.

Mr Sarfraz Khan and Mrs Jyoti Khan (second from right) with their children, Ayaan Khan, Aleena Khan and Aliya Khan (left to right).

PHOTO: COURTESY OF JYOTI KHAN

Schools remind parents that exams are not the be all and end all, said Ms Khan, but the pressure is constant, amplified during conversations with others.

She tried not to pass that anxiety on to her children, now in Secondary 4 and 2, and Primary 2.

Yet, when her son applied to a secondary school through the Direct School Admission (DSA) pathway – which allows children to apply to schools through their non-academic strengths – she found herself helping him polish guitar pieces and write personal statements.

Associate Professor Vincent Chua, who teaches sociology and anthropology at the National University of Singapore, said competition persists because demand for “good schools” outstrips the supply.

“Even though the new PSLE (scoring) system is designed to be non-competitive… the distribution of schools still follows a curve: a small number of elite schools, a majority of good ones, and a few that are less sought after,” he said. “As long as this hierarchy exists, competition will persist.

“The ideal, where every school is seen as a good school, remains some distance away.”

Parents feel compelled to invest in tuition, enrichment, and constant monitoring, Prof Chua said, adding that exams become more challenging to distinguish top performers.

When education becomes a contest, social comparison becomes a way of life, he said. “The result is an escalating arms race that breeds stress, burnout, and declining youth well-being.”

People still judge others based on the schools they went to, said Ms Khan. “I’ve seen it.”

Many still believe that a child gains more from going to a good school – apart from being affiliated with a brand name, they get access to social and alumni networks, she added.

This strain continues as children move through the system, intensifying at major exams like the O, N and A levels – seen as gateways into higher education.

For tutor Siti Aishah, 60, whose daughter just took the N levels, the culture of comparing children by their academic achievements has become toxic. “Especially when you have family gatherings and everyone starts all the comparisons: ‘Hey, what’s your son doing?’”

Her older son went to a polytechnic and has been accepted to a local university.

But her daughter often compares her results with her brother’s, and worries that going to ITE means she might not get into university, she said.

Madam Aishah has sought to reassure her daughter, and told her: “Come what may, the results we accept. Because you are you, and your brother is your brother. You two are different.”

The former teacher feels there are now more pathways for students, and with hard work, children can overcome early setbacks and find their way.

Over the years, the Government has introduced more routes to reduce reliance on single exams and assess students more holistically.

More changes have also been promised.

The Ministry of Education (MOE) in May said efforts are ongoing to refine the DSA selection process. Former education minister Chan Chun Sing said in January that this will be part of a review to ensure that schools focus on students’ development, that the selection process is objective and transparent, and DSA continues to be accessible.

DSA was started in 2004 to allow students to enter secondary school on other merits such as sports, arts or leadership. Other schemes followed, allowing students to secure polytechnic places before sitting major exams – though they must still meet minimum entry and GPA requirements.