SINGAPORE – The House of Tan Yeok Nee at 101 Penang Road – the sole survivor of Singapore’s Four Grand Mansions built by Teochew tycoons in the 1800s – will welcome the public on Nov 1 in a grand opening after extensive restoration works that took nearly four years to complete.

Standing proudly at the heart of Orchard Road, opposite The Istana, the building is a testament to the city’s memory, culture and identity, echoing ancestral stories through its gilded woodwork and intricate mouldings.

Considered by conservation experts as a masterpiece of Teochew architecture, the property is being reimagined by its new owner, the Karim Family Foundation, as a lifestyle hub with dining and entertainment options to be enjoyed by Singapore residents and visitors.

The foundation is the philanthropic arm of a group of companies owned by the Indonesian-Chinese Karim family, led by palm oil tycoon Bachtiar Karim.

The foundation’s director and principal Cindy Karim, 34, oversees the foundation’s charitable initiatives focused on four pillars: sports development; arts and culture; mental health; and education. She is the daughter of Mr Karim.

The house, which was declared a national monument in 1974, was sold to the Karim family in March 2022 for an undisclosed sum believed to be somewhere between $85 million and the asking price of $92 million. Including restoration, market watchers say the project easily cost more than $100 million.

The sellers were integrated real estate and healthcare company Perennial Holdings and asset management firm Charles Quay International. Each held a 50 per cent stake in the property.

In a statement to the press at the time, marketing agent Savills Singapore said the expression of interest in the property was overwhelming, with inquiries from many new buyers from countries such as China, Indonesia and India.

The double-storey building sits on a freehold site spanning 26,321 sq ft. It includes a central residence with two courtyards and a periphery of spaces that have been converted into offices for the Karim group of companies.

Intricate timber carvings gilded with 24K gold foil and finished with patina coating.

ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

The project was awarded by the foundation in January 2022 to DP Architects (DPA).

DPA worked closely with conservation consultant and Associate Professor Yeo Kang Shua, who is the associate head of pillar for research, practice and industry at the Singapore University of Technology and Design.

An intricately painted ceiling beam.

ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

Ms Karim, who has lived in Singapore since 1998 with her family, says that as an undergraduate at the Singapore Management University, she was always intrigued by the house’s ornate ridged roof and imposing facade when she drove past on her way to school.

“When it came up in late 2021 that the property was on sale, my family and I were very excited to make a bid for it,” Ms Karim tells The Straits Times in an exclusive interview from her office in one of the newly renovated rooms in the House of Tan Yeok Nee.

The family worked with DPA and Prof Yeo to restore the entire building to the original 1800s vision of towkay (Hokkien for business owner) Tan Yeok Nee, sparing no expense.

“The building has had so many incarnations in its 140-year history – a station master’s residence, the headquarters of the Salvation Army and two educational institutions – but it has never been truly open to the public to enjoy,” Ms Karim says.

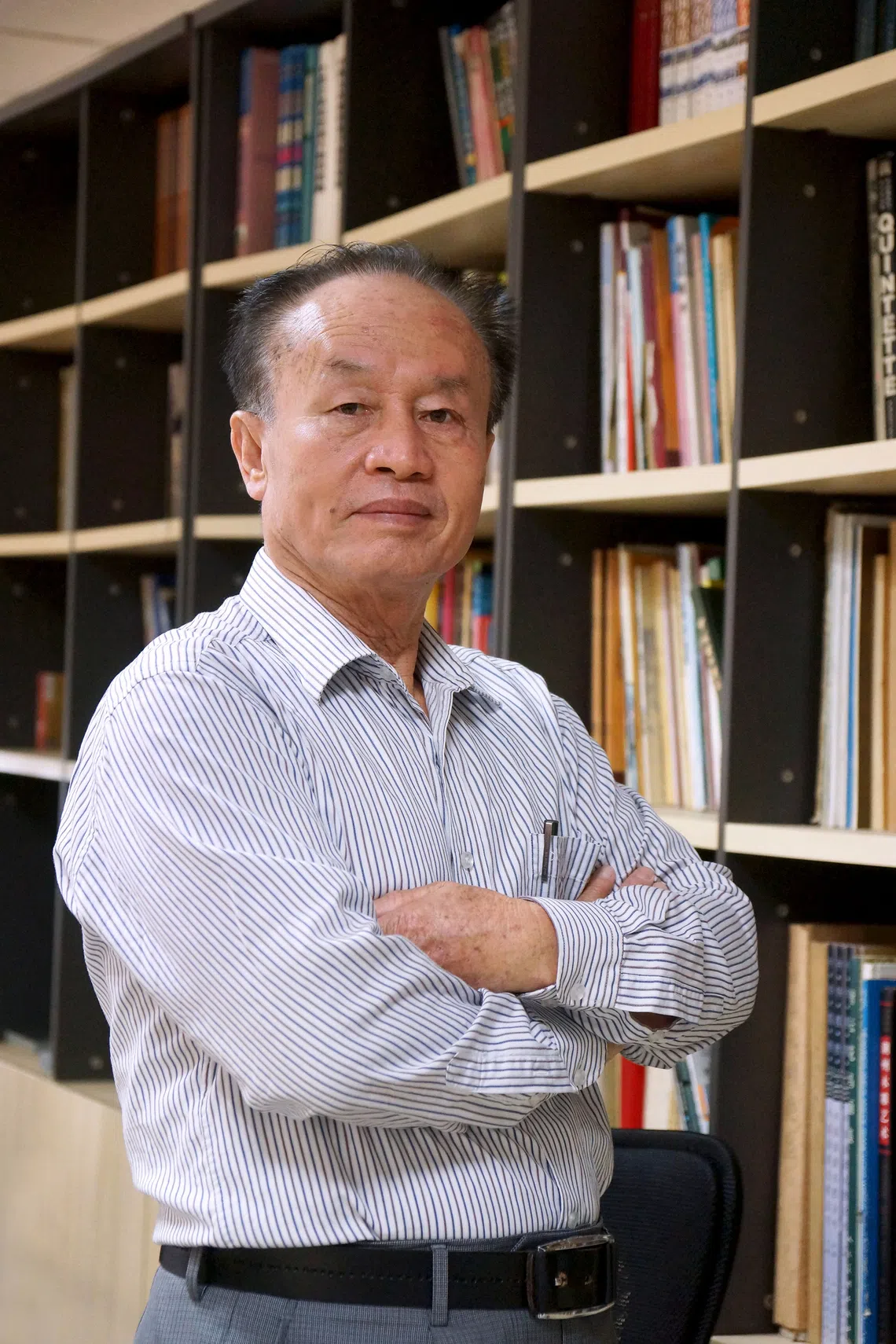

Ms Cindy Karim and her family made a bid for the House of Tan Yeok Nee in late 2021.

PHOTO: LIANHE ZAOBAO

“We wanted to authentically restore the house to just as it was in the 1800s, while also envisioning the space to be accessible for the public – with galleries and a restaurant – to allow visitors to not only step back in time, but also enjoy the house in new ways.”

In the line-up for the grand opening on the weekend of Nov 1 and 2 is a new Heritage Gallery featuring Singaporean artist Tan Ngiap Heng, the great-great-grandson of Tan Yeok Nee, who will present two series that explore ancestry and identity.

There will also be a photography exhibition by the Teochew Sim Clan and guided tours of the house led by docents from the Society of Tourist Guides (Singapore).

On Nov 6, the Loca Niru restaurant opens. The 36-seat fine-dining concept on the second level, by Gaia Lifestyle Group, is helmed by rising chef Shusuke Kubota, who pairs Japanese flair with French techniques.

DPA’s senior associate Shawn Teo and architectural executive Jiang Wenhuan flew to Chaozhou prefecture, China, in October 2023 with key staff from the Karim Family Foundation and a team of consultants to arrange for 30 skilled craftsmen, who included 20 masters of Teochew architecture, to come to Singapore to work on the restoration.

Gilded timber carvings along the beams of the house.

ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

Since its completion in 1885, the house has changed hands several times, along with numerous alterations to its original design.

First, around the turn of the 20th century, the house was briefly acquired by the British colonial government to house the assistant manager of the Tank Road railway station.

According to the National Library Board’s Singapore Infopedia online platform, Mr Tan’s family left in 1902 due to the noise and dust from the construction of the nearby railway. Mr Tan died later that year in China at the age of 75.

When the railway staff moved, the government placed the house in trust for the Anglican bishop. In 1912, it became St Mary’s Home and School for Eurasian Girls.

The main hall’s timber roof is supported by single-piece octagonal granite columns.

ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

In 1938, the Salvation Army took over and used the house as its headquarters from late May that year. After the ravages of World War II, the house underwent extensive repairs by the charitable organisation.

Later, around the years 1999 and 2000, there was a full-scale conservation effort by RSP Architects Planners & Engineers. It involved more than 100 craftsmen, who restored original decorative features, gable wall artworks, wood carvings and gold woodwork.

Work started in early 1999 to convert the house into the Asian campus of the University of Chicago’s Graduate School of Business in a $12 million preservation and renovation.

The house, together with the former Cockpit Hotel, was bought by a consortium led by developer Wing Tai Holdings in 1996.

The conservation effort won the house the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s Architectural Heritage Award in 2001.

In 2022, the house served as the campus for higher education institution Amity Global Institute before the property was acquired by the Karim Family Foundation.

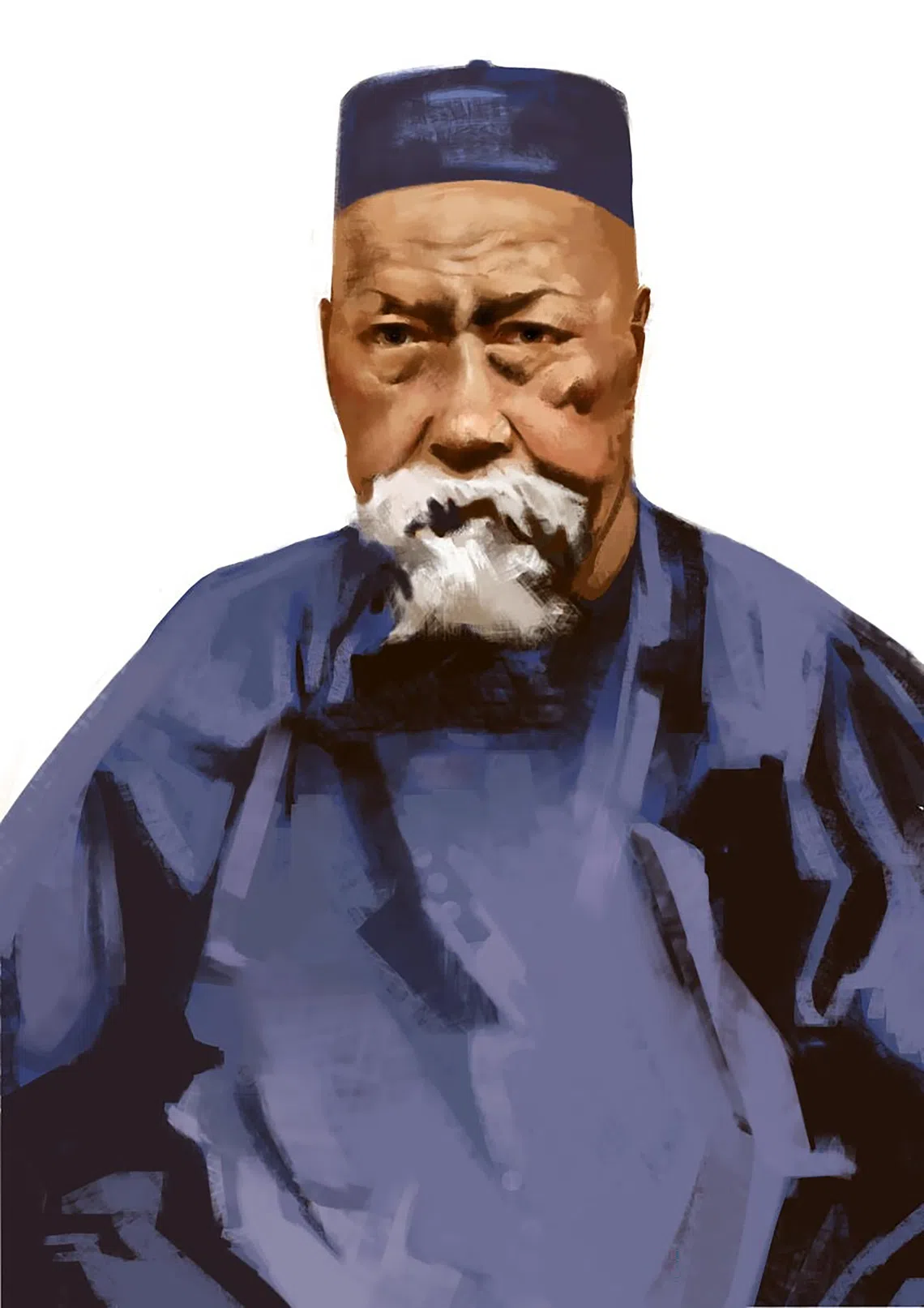

From 1882 to 1885, Mr Tan had overseen the design of his Singapore house in Tank Road (now 101 Penang Road) as a homage to his larger ancestral mansion in Chaozhou.

Born in 1827 in the Jin Sha village in Shang Pu (present-day Caitang), Chaozhou, the young Mr Tan left China to seek his fortune in South-east Asia, then commonly referred to as Nanyang. He later set up gambier and pepper plantations in Johor, Malaysia.

His Tank Road house was modelled closely on Cong Xi Gong Ci, the grand cluster house he had built for his Teochew clan in Jinsha Xiang, Chaozhou. It is believed to have been completed around 1884, about a year before his Singapore courtyard mansion was built.

Both houses are showcases of traditional southern Chinese architecture, with two large central halls separated by wide courtyards.

Auspicious flora and fauna of Chinese culture are displayed, such as orchids to denote resilience, bats and koi to symbolise abundance, and dragons to impart luck and prosperity.

A hallmark of Teochew design can be seen on the roof ridges, which feature intricate timber carvings, plaster reliefs and porcelain figurines created through a decorative process called “qianci”.

A rainwater drainpipe concealed with plaster bas-relief of a Chinese parasol tree.

ST PHOTO: LIM YAOHUI

Skilled artisans, mainly from Chaozhou, use shards made from fired bowls to create mosaic patterns and classical Chinese figures on roof ridges and bas-reliefs on walls to depict Chinese people’s aspirations through richly ornamented surfaces.

A gilded fascia board along the roof eaves.