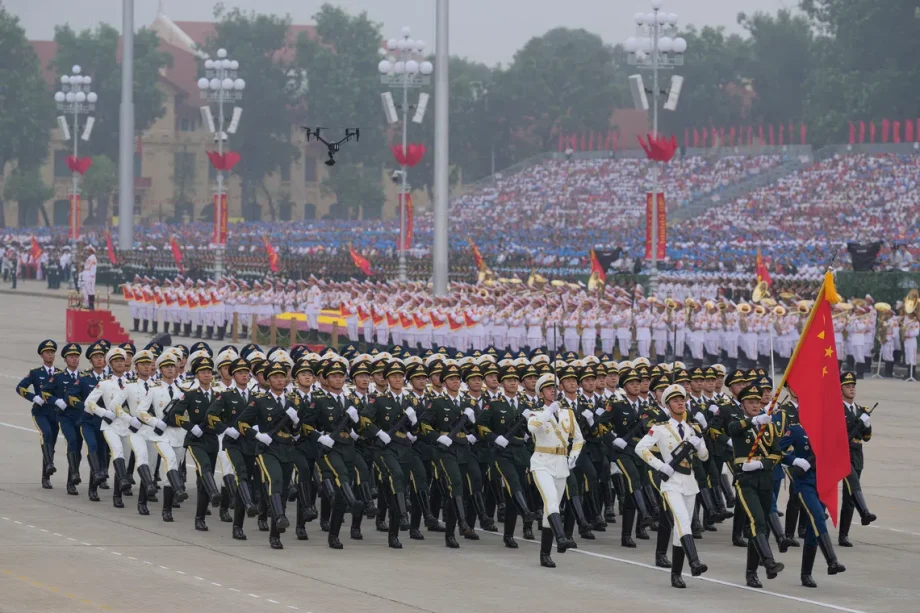

HANOI – Dozens of young Vietnamese women lined up for hours in September to catch a glimpse of “cool” troops marching through Hanoi in a huge military parade. But it was not their own soldiers they were looking out for. It was the Chinese contingent.

The scene reflects a shift in attitudes towards China – amid trade tensions with the United States – which has allowed Vietnamese leaders to push forward with sensitive projects, such as high-speed rail links and special economic zones close to China, that may significantly boost bilateral ties.

Only a few years ago, with many Vietnamese wary of a powerful neighbour with which they have fought multiple wars, such projects were seen as too controversial and caused violent protests.

But views are softening, posts on social media, online searches and language learning data show.

Nearly 75 per cent of Vietnamese respondents prefer the US to China as a partner, but the share favouring China is rising faster than anywhere else in South-east Asia, bucking the regional trend, according to a poll conducted at the start of 2025 by the Singapore-based ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute.

Social media appears to be playing a crucial role in the changing mood in Vietnam – and in particular TikTok, which is popular among youth and in 2024 had 67 million users in Vietnam, the highest number after Facebook, according to the government.

When users of the platform owned by Chinese tech giant ByteDance search for the Vietnamese word for China, they get overwhelmingly positive results, some of them dating back to 2023.

Among popular videos suggested by TikTok are clips of Chinese soldiers performing synchronised dances and videos showcasing Chinese cities, with many viewers expressing admiration for China’s rapid development.

TikTok users searching for the Vietnamese name of the South China Sea, a frequent flashpoint between the two communist countries that have competing claims over the waters, often get clips on tropical storms or tensions between China and the Philippines, which also has claims on parts of the sea, according to tests conducted without user profiles to avoid algorithmic bias.

TikTok’s algorithm is confidential. China has orchestrated online campaigns using fake accounts on platforms including TikTok and Facebook to promote its geopolitical interests in the Philippines.