SOLO, Central Java – The squat, one-storey school building near the Bengawan Solo (Solo River) appears unremarkable from the outside. Inside, rows of bunk beds line former classrooms, the blackboards and chalk replaced with simple shelves and medicine boxes.

This is home to 19 children born with HIV. In a second house across town live another 17 such youngsters. All depend on three volunteers, and a patchwork of private donations, to stay afloat.

When The Straits Times visited the school-turned-shelter on Nov 28, the children were mourning the recent death of 17-year-old Siti Safia (not her real name).

She had, unbeknown to her carers, stopped taking her antiretroviral (ARV) pills, resulting in a month-long hospital stay and complications leading to meningitis.

“We found many pills hidden under her bed,” said Mr Puger Mulyono. “She held them under her tongue and spat them out later,” said the 51-year-old volunteer, whom the children affectionately call ayah, which means father in Bahasa Indonesia.

Siti was the latest of the 26 residents at the two shelters who have died since 2012.

Her life, and death, underscores the fragile lives inside these modest shelters – and the lack of consistent state support for people living with HIV in Indonesia.

Indonesia has an estimated 564,000 people living with HIV as at 2025, according to the Health Ministry. About 65 per cent of these know their status, and just 255,000 receive ARV treatment, which is free in public health centres but unevenly available. Fewer than half of the country’s 13,700 facilities dispense the medication.

“All health facilities (in the country) will have HIV antiretroviral drugs in the next several years. We aim to achieve a 95-95-95 target by 2030,” Ms Prima Yosephine, the Health Ministry’s director of health surveillance and quarantine, told ST on Dec 4.

That target is a global goal for HIV epidemic control, which aims for 95 per cent of people living with HIV to know their status, 95 per cent of those diagnosed to be on antiretroviral therapy, and 95 per cent of those being treated to achieve viral suppression.

But progress is stymied by resource constraints and shrinking foreign support. In particular, funding for Indonesia’s health programmes was hard hit by the

Trump administration’s

freeze

on foreign aid

in January 2025.

Now, more than ever, the growing gaps resulting from funding cuts and a lackadaisical government response to HIV/AIDS are being addressed by Indonesia’s network of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), community-based organisations and individuals in a display of remarkable private goodwill and quiet heroism. These groups and volunteers provide essential services, advocacy and support in the face of limited resources, state inaction and high levels of stigma.

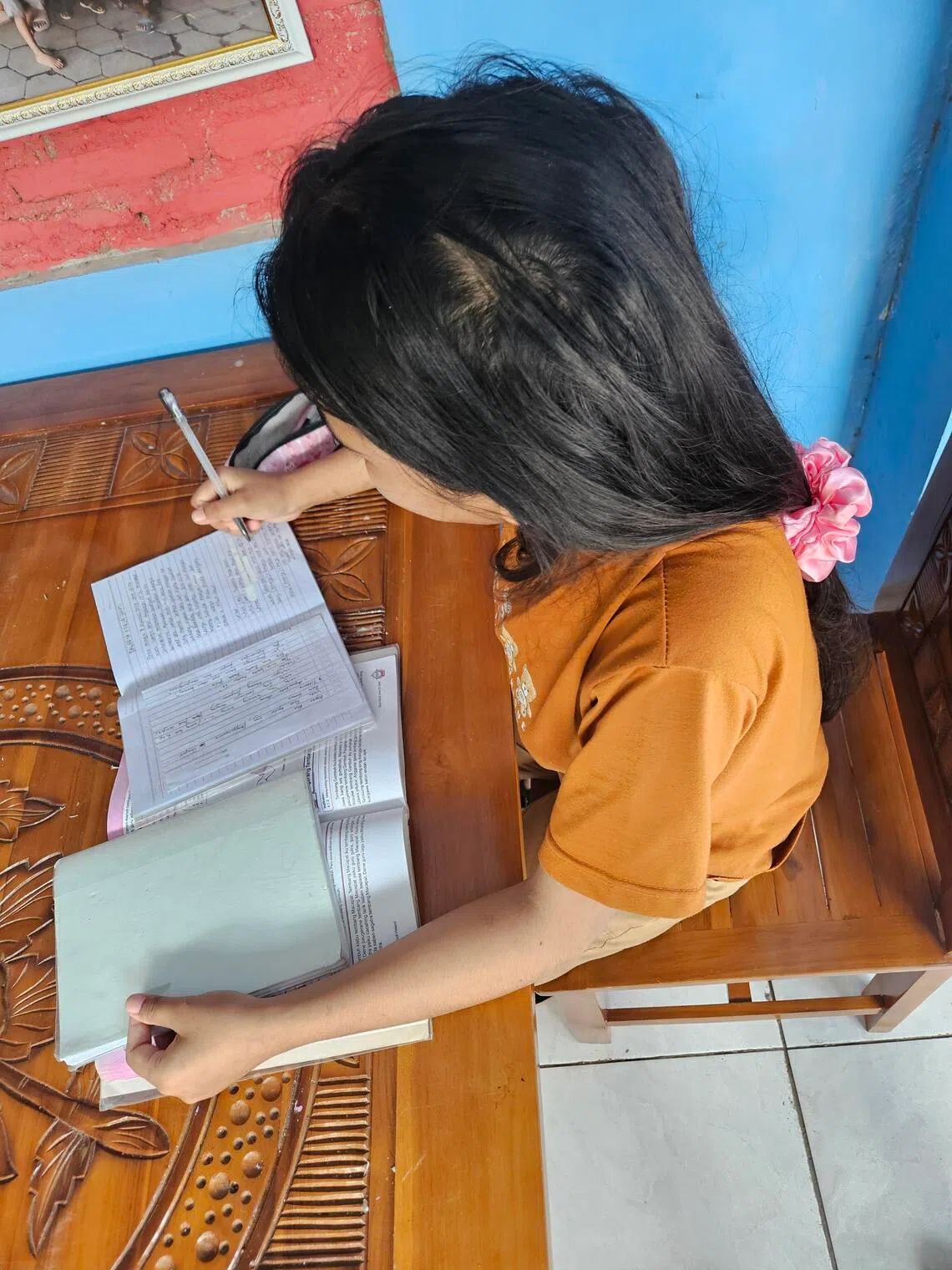

Children playing cards in the corridor outside a classroom, in a repurposed school building in eastern Solo, Central Java.

ST PHOTO: WAHYUDI SOERIAATMADJA