SINGAPORE – Fewer than 500 people worldwide are known to have a rare genetic disorder called GNAO1 mutation, which disrupts brain signalling and affects movement and development.

So it is no wonder that 11-year-old Adrian’s involuntary, jerky movements and developmental delays were initially attributed to cerebral palsy – a group of conditions affecting movement and posture caused by damage in the developing brain, most often before birth.

His mother Felicia Tan, 43, told The Straits Times that he was born prematurely at 34 weeks and was in the neonatal intensive care unit for three weeks.

“It was a non-event except for a hole in his heart that was resolved with medication,” she said.

But when Adrian was nine months old, he was not hitting any of the milestones typical for babies his age. He was not sitting up without support, crawling or babbling repeated syllables like “mama, mama”. “He was also non-communicative, and was initially diagnosed with cerebral palsy and treated as such until he was 10 before being referred to KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH),” Ms Tan said.

His condition got serious when he was infected with influenza A in June 2025. He developed high fever and bad tremors that started from his legs.

“We took him to NUH, which was the closest to our home. He tested positive for influenza A and was given Tamiflu and discharged,” his mother said, referring to the National University Hospital.

Despite the medication, Adrian remained sick, “lying very still on his bed”. “He could not move or sit up. Then, close to two weeks later, the abnormal repetitive shaking started from his legs. They were not under his control… He was so stiff we could not even fit him into his wheelchair,” she added.

That was when Ms Tan’s sister-in-law, who works at KKH, introduced her to paediatric neurologist Simon Ling. Adrian was admitted to the hospital in mid-2025, and he underwent genetic testing.

In July, he was diagnosed with GNAO1 mutation, which affects a group of proteins, turning them into molecular “switches” in the brain and disrupting normal signalling.

Doctors said children with this condition often suffer from severe movement disorders, muscle stiffness, and developmental delays – symptoms that closely resemble those of cerebral palsy. Only genetic testing can confirm it.

According to medical literature, the first children with GNAO1 were diagnosed only 12 years ago in 2013 by a Japanese research team studying DNA mutations in four Japanese children. After Adrian’s diagnosis, Dr Ling introduced Ms Tan to Dr Yeo Tong Hong, a visiting paediatric neurologist at KKH, who felt that the boy was the right candidate for deep brain stimulation surgery.

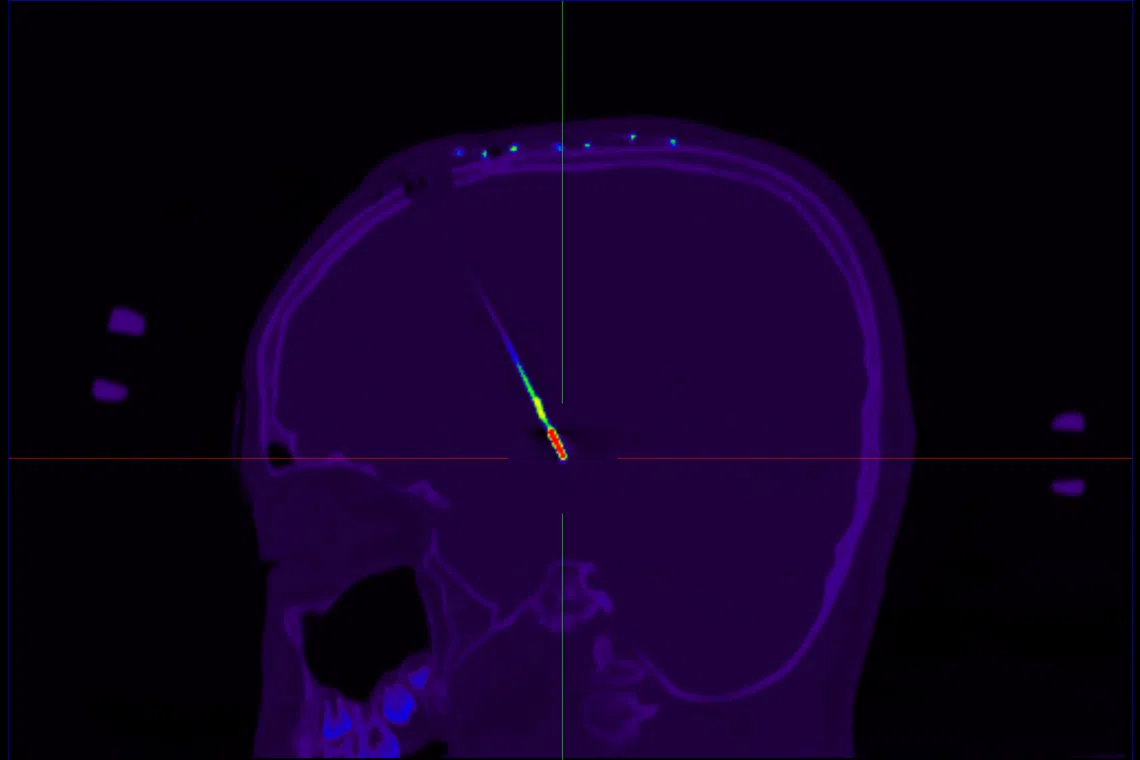

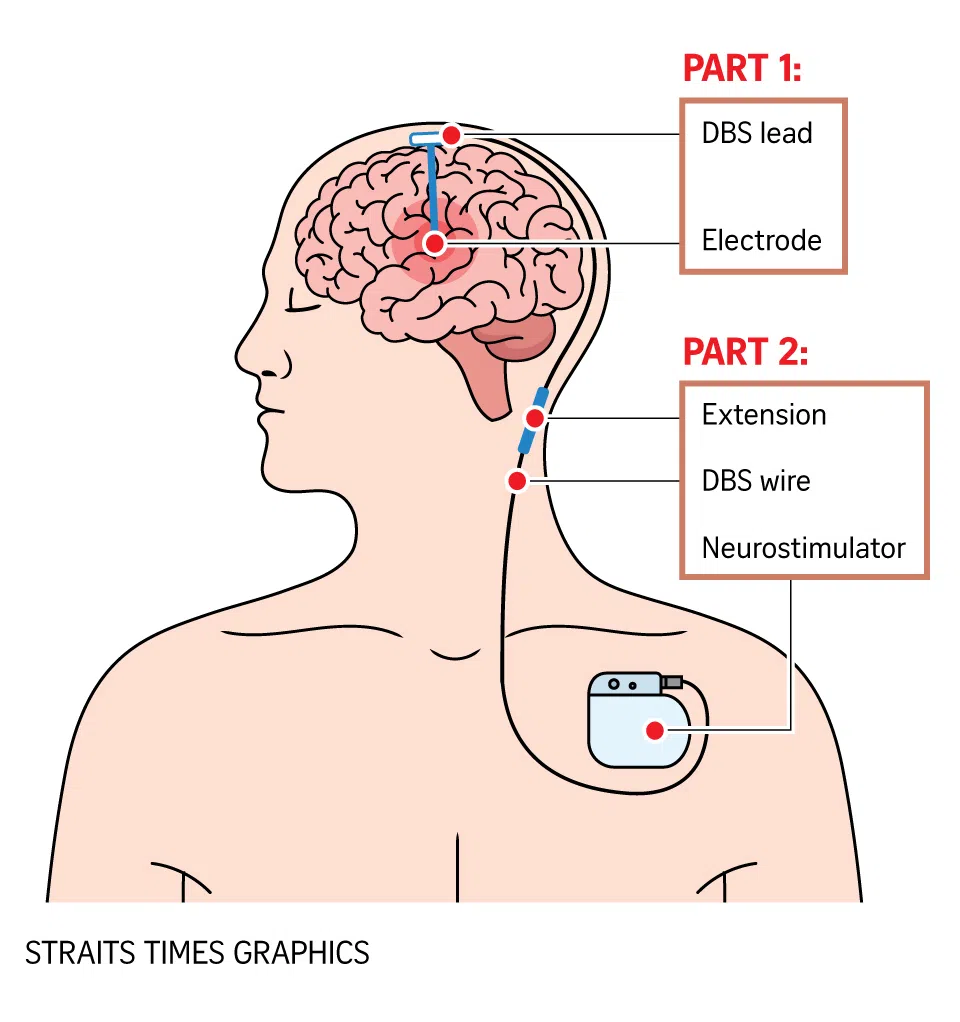

“It is an advanced treatment that involves placing two very thin wires (electrodes) into specific areas of the brain. These wires are connected under the skin to a small (battery-operated device) usually placed in the chest or the abdomen,” said Dr Yeo, who practises at Parkway East Hospital. The device is about the size of an Apple smartwatch face.

Adrian and his mother Felicia Tan with neurosurgeon Nicolas Kon from Mount Elizabeth Hospital (left) and Dr Yeo Tong Hong, a paediatric neurologist from Parkway East Hospital.

ST PHOTO: NG SOR LUAN

Called a pulse generator, it sends tiny electrical signals to help correct the brain’s activity and reduce symptoms, especially dystonia, a movement disorder characterised by involuntary, sustained muscle contractions that cause repetitive twisting or jerking movements and abnormal postures. The device works “much like how a heart pacemaker works”, neurosurgeon Nicolas Kon explained.

Since deep brain stimulation helps manage movement symptoms, it is also used to treat Parkinson’s disease when medications become less effective. Studies have shown that it tends to be most effective in primary dystonia, a group of movement disorders caused by specific genetic changes.

“In these cases, brain scans usually look normal, with no injury or scarring, and treatment response rates can be as high as 90 per cent,” Dr Yeo said.